Author: Ángel Hernando Gómez – Translation: Erika-Lucia Gonzalez-Carrion

When we formulate hypotheses or set objectives, it is normal, from the point of view of the human being in general and of the researcher in particular, that we hope to reach our objectives or confirm the hypotheses we propose, it is clear that a confirmed hypothesis is better than one that is not confirmed.

Although in most of the research designs we propose, we confirm the hypotheses and / or achieve the objectives, it does not always have to be that way, and in fact it is not, so the temptation to “force” (temptation that goes to both the new and the not so inexpert researchers) the analysis or hide the anomalous results that appear – when we make the analysis of our results at the end of the field work – it is great. We can never fall into this temptation for at least three reasons, the first and simple is because it is unethical, the second because we would be missing the truth and the third is because, on numerous occasions, these unconfirmed hypotheses can be more enriching for the subject matter that the simple confirmation of what was considered. If the hypothesis has been confirmed, the conclusion is clear since the research question has been answered, but if it has not been confirmed we have a new opportunity to investigate, to make new questions or to reformulate some of those that we had already done ourselves.

Although in most of the research designs we propose, we confirm the hypotheses and / or achieve the objectives, it does not always have to be that way, and in fact it is not, so the temptation to “force” (temptation that goes to both the new and the not so inexpert researchers) the analysis or hide the anomalous results that appear – when we make the analysis of our results at the end of the field work – it is great. We can never fall into this temptation for at least three reasons, the first and simple is because it is unethical, the second because we would be missing the truth and the third is because, on numerous occasions, these unconfirmed hypotheses can be more enriching for the subject matter that the simple confirmation of what was considered. If the hypothesis has been confirmed, the conclusion is clear since the research question has been answered, but if it has not been confirmed we have a new opportunity to investigate, to make new questions or to reformulate some of those that we had already done ourselves.

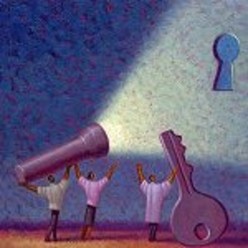

In the course of our investigations, sometimes we find anomalous or unexpected results, these should never be hidden (it may be a serendipity and we are faced with a very valuable finding that we have reached, without looking for it, accidental!) as we are directly opening new research proposals, new lines in which we can design research to try to respond to what we did not expect but that has appeared in our results. These anomalous results have to be brought to light and we have to give them the best possible explanation or, simply, say that we have found them and, for now, we can not give them any explanation. It can also happen that, if we do not show these results, the editor, who in many cases is or must also be a good researcher, will be the one who brings them to light.

We must also learn from the unexpected, what in advance can be considered as a failure or a weakness of our research is not so, we can consider it a strength because it allows us to formulate new hypotheses or propose new research objectives (we or any member of the academic community that works or investigates on this subject) that, in the end, what they will do is to enrich the research on the thematic field. This strength can only be given, obviously, if instead of hiding them or “putting them in a shoehorn” we are able to “bring to light” the anomalous or unexpected results that we find in our researches.